Ferdinando Vichi Artist Biography

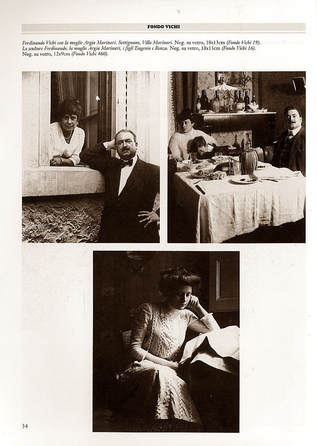

Photos: Ferdinando Vichy and his wife, Argia Marinari

Photos: Ferdinando Vichy and his wife, Argia Marinari

The following biography is adapted from an article written by his great-nephew, the Italian writer Marco Vichi, who, in turn, refers to an article in the newspaper Il Telegrafo, published 2 November 1932.

Discussing the life of an artist like Ferdinando Vichi is difficult. Despite being amongst the greatest sculptors of our age, especially as a portraitist, he was shy and almost backward in the face of every form of publicity.

He was born into a noble family in Florence in 1875. In the early nineteenth century his grandfather founded the Gallerie Vichi, which soon became famous, especially abroad, and was later directed by Ferdinando himself. One of the Vichi Galleries headquarters was the Art Nouveau building of Via Borgo Ognissanti - two others were in Via Tornabuoni and on the Lungarno Vespucci. From his childhood he was passionate about art, and soon entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence under the guidance of Rivalta and Zocchi, where he won numerous prizes. Still very young, he exhibited his work, La bagnante, at the Paris Salon, his works selling immediately.

Later he worked in Germany, France, England, the two Americas and India. The international criticism speaks of the young Vichi - not yet twenty years old - "with exceedingly flattering judgments". In the competition for the portrait of King Umberto for the Venice Chamber of Commerce, he was chosen, together with two others, out of sixty contestants, but in the final phase the competition was abolished "for the artistic reason that the king wanted to entrust the execution of the bust to a Venetian".

There are many portraits of important characters made by him on commission, including three American presidents, MacKinley, Roosevelt and Taft, and also the Queen of Baroda. He also made numerous monuments to the fallen in many Italian towns, the monument to Senator Donato Marelli and a large number of tombs in England, Switzerland and America (among the most notable for the Bally, Phillips and Rawleigh families).

Ferdinando Vichi won grand prizes and gold medals in various Italian exhibitions (including those of Venice and Livorno). In 1907, at the age of thirty, he was awarded the title of Knight of the Kingdom. He then worked on the busts of Marshall Cadorna and Mussolini. This last portrait, depicting the duce in a simple Roman tunic, is praised by the critic of The Telegraph - already mentioned above - and is defined as "the most beautiful to date has been performed to eternal the effigy of the sacred Man for the destinies of Italy (...) without mannerism of style (...) with Michelangelo's sobriety (...) and really no other bust like this of the Vichi would be worthy of being known and reproduced, where the image del Duce has to be memory, incitement, command". This bronze, together with the plaster, has unfortunately been destroyed in a period that was not inclined to distinguish politics from art.

Of his other numerous works, the Vichi family currently possesses a large number of plaster casts (also in bas-relief) and some bronze pieces; the subjects, the poses, the same realisation (attentive to reproducing reality) are part of a nineteenth-century culture, certainly not an innovator (think about his contemporaries or even earlier sculptors such as Medardo Rosso, Boccioni, Rodin and others, who had already broken - each in their own way - the rule of fifteenth-century figurations). Equally, in his sculpture there is a passionate skill and a harmonising force that dominates the forms, both in the busts and in the tiny clay sketches. When the subject is unique - a bust, a whole figure - we find the harmony in the pose itself, otherwise, when the central human figure is placed next to another, whether an animal or a a simple table, Ferdinando always finds a balance, an essential reciprocity between the elements depicted that, by uniting, become a new unity, aesthetically inseparable. Linked to the figurative art of the Macchiaioli, the sculptor Vichi almost never tends to represent symbolic or exemplary occasions, but rather wants to capture the intimate and daily moments, often trying to stop the movement of his figures in a thoughtful or reflective pose, an occasion of a solitary moment - an occasion almost always customary, almost never rhetorical.

In the cemetery of S. Miniato al Monte, high above Florence, there are tombs of the Vichi family with bronze busts made by Ferdinando, including those of his father, Orlando and a cuginetta who died at the age of six years.

Photography, for Ferdinando, was initially a need for work. He needed images of models, horses and others, which he often photographed himself; from America came requests for portraits in bronze accompanied by one or more photographs. Later it became a parallel interest, perhaps amateurish, but certainly exciting for him. In addition to the numerous family groups, there are many of his portraits of Florence. They strike for a way of blocking the casual event that immediately denotes an intention, a precise cut. The objective becomes the hidden eye of a spy, or rather ‘a quick glance’, then goes further: he does not want to influence, intervene, prepare the event for the shot. Unseen, you want to stop that certain moment and take it away, keep it. And that certain moment is not chosen because it is special, because it is meaningful in itself, but rather for the opposite, it is a common moment which is given the possibility of becoming special - stuck in an image just for its neutrality. And again, that instant actually appears as a real fragment of a real movement - not adulterated, distorted, but rather independent, unaware of being spied on and desired. Sometimes - so the ‘normal’ moment is stolen from the world - the impression is that the image was produced by itself on the plate, without any will behind the machine, no eye to choose the place and the moment - or perhaps without the presence of the same machine: so, at a distance, by magic.

To take a closer look at the figure of Ferdinando Vichi however, I have to go beyond this biographical summary and draw from the anecdoes handed down through the family, a sort of dusty but authentic mnemonic chest.

Ferdinando had a reputation as a witty man, furnished with prompt and pungent words, but generous and simple, never acrimonious. He loved jokes, he organized diabolical ones. He knew how to involve dozens of people, a whole crowd, on a ridiculously prepared opportunity. Then he tasted the results, grinning silently inside his chest, betrayed outside only by the rhythmic sway of his enormous abdomen.

In another article - written for the trigly of his death - I read: "(...) the mottos and the frizzi flourished from his lips as the gentle figures of girls, of putti, of keeping their children grieving mothers come out of his hands breast, of tender youths ". Ferdinando always carried with him a tiny pencil (which disappeared in his fingers), an equally small rubber, a block.

Wherever he could be seen drawing: portraits, but also caricatures - one of which cost him a friendship. He also abandoned himself to some caricatural sculpture, where he was able to free himself, perhaps, from interpretations that he never wanted to seriously attempt in his official profession. Moreover, despite all that his work, he knew how to find the time - and this I like - to portray his servants, always men of mind too simple and fond of the artist, good until idiocy - and the plaster of one of those faces still exists.

"There was the patron in him" -continua the writing- "and everyone gave: they were sometimes artistic aid, advice to young people who frequented his study and wanted him master, on other occasions they were also considerable material supports that widen to friends ". Here and there are laudatory phrases, such as: "(...) one of those artists who conceived art for art, who conceived it as a true enjoyment of the spirit (...), a good Tuscan race artist, did not know so much , bitterness, disdain (...) smiles, good and serene words that aroused sympathy in those who approached him (...) was a dreamer of justice and brotherhood ". Beyond the rhetoric (which we can comfortably, let's say, expunge) is undoubtedly the portrait of a pleasant individual, of remarkable personality.

In one of his villas - that of Settignano, still solid today, looking out over Florence - several relatives met every Saturday: they spent the afternoon in the park, organized games, played the piano and sang; then the ladies were apart, gossip began, and a great deal of talk of hats and dresses-the gentlemen were discussing the news of the time, they were polemics about politics, they smoked.

It is in this Settignano villa that the most photographs were taken, both outdoors and indoors. Among the guests, often, could be found the literary and true sisters Materassi, who lived in Ponte a Mensola, a rifle shot by the Vichi - and maybe they too, on some occasions, stiffened under a big white hat waiting for the shot of Ferdinando's machine. Another friend passed by the Vichi villa: Primo Conti's father. Ferdinando - not a hunter - he often loaned his father Orlando's carbine to go hunting. Ferdinando's son, Eugenio (painter, but above all an art expert) and Primo Conti continued the friendship of their fathers.

But let's go back to Ferdinando.

A man with a huge body (in his youth he enjoyed competing with his friend and famous world champion of the Greco-Roman fight, Giovanni Raicevich, of whom he withdrew an arm with his muscles contracted) he happened to be observing four porters who were busily discussing the system better to transport the block of Carrara marble, which he ordered, to his studio in Piazza Cavour (today Piazza della Libertà). The four were trying to get organized to make the grandepartment move up a large ladder, but no one started the business.

- "Just you, master" said one of the porters seeing Ferdinando appear "Tell us: how would you do?"

- "So" he did, and entrusted the jacket to one of the four and rolled up his sleeves carried with his hands the marble to its destination, making it sway and climb step by step.

- "Thank you maestro" said the porters "Thank you so much!"

- "And of what?" he marveled - and with the usual system he brought the block back to the foot of the steps, took off his jacket and left.

But the episode that most binds him to my memory is his famous "deal", with which he swapped a famous hotel in Florence with a magnificent canvas of the late sixteenth century (attributed to Pordenone) that still belongs to the family ...

"I took great weight" he said to his wife, satisfied. Wandering in the infernal circles I could not decide where to go looking for it, but certainly I would be tempted to spy behind the back of the great verma Cerberus. He was certainly a gourmet, without regrets. At good food, he sacrificed health consciously. Taurine neck, huge hands, with a narrow heart in the fat continued his pilgrimages between desserts and dishes. The doctors who offered him the odious crossroads between abstinence and death replied that he could not think about it now, because the next day he was invited to a dinner.

On Christmas Day 1941, aged sixty-six, the family doctor visited him in bed, and for the umpteenth time he recommended that the sculptor set off on the path of gastronomic morigeness. Only a healthy life, he said, can save him. "Why live suffering?" Ferdinando asked. Then, as the doctor left the sculptor's villa (still laughing at the unrepentant joke), he was urgently called back. The patient was dead. His heart had not been able to extricate itself from those fat reticulates.

I wrote this succinct portrait of Ferdinando Vichi with pleasure, because always, although I never met him in person, his figure has aroused sympathy.

|

|

PHOTOGRAPHY Photography, for Ferdinando, was initially as a record of figures that he used as models for his work but later he became a keen photographer. In 1964, the Vichi family donated photographic plates made by the Florentine sculptor Ferdinando Vichi to the Archivio Fotografico Toscano di Prato. CLICK THIS LINK TO GO BACK TO COURTING COUPLE MARBLE |

REFERENCES

Archivio Fotografico Toscano di Prato, Magazine N°: 10, June: 1989

several photographs by Ferdinando Vichi.

http://www.tuttartpitturasculturapoesiamusica.com/2015/09/Ferdinando-Vichi.html