The Nest

|

Research by Jacqueline Arundel

|

|

Acc No 215

Artist John Everett Millais (after) Artist dates 1829-1896 Engraver George H Every 1837-1910 Medium print Size unknown Date produced original painting 1887 Donor Frederick Treasure (1871-1949) Date donated 24 December 1945 |

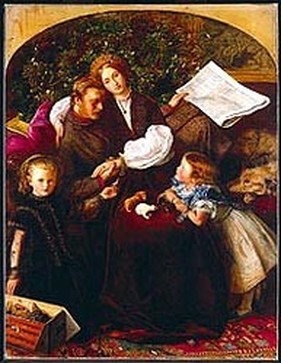

The Nest by John Everett Millais

The picture in the Collection is a monochrome print of Millais’ original painting,1887. It is typical of Millais' late sentimental subjects.The printmaker responsible for 215 “The Nest” after Millais is now known to be George H Every and its date recorded as 1890. The British Museum describes him as a 'nineteenth century mezzotint engraver who exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1864'. It has another example of this print which verifies these details: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1893-0718-21. Records at the National Portrait Gallery show that George Every (1837-1910), a London born mezzotint engraver who exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1864-1905, was associated with 56 of their portraits.

'The Magazine of Art' described the painting as:

"suggestive of the Christmas number style of art, dry, disagreeable in colour and steeped in the tritest kind of popular sentiment".

'The Academy Journal' critic wrote:

"there are excellencies of a very high order especially in the head ... but here too a cheapness of sentiment, an obvious disinclination

to deal with the higher elements which even such subjects contain can detract from the enjoyment afforded by the easy mastery of

technical difficulties".

Despite increasingly severe criticism by informed observers, Millais' paintings continued to sell well, as they were calculated to appeal to prospective buyers. The original painting was purchased from the artist by Thomas Agnew & Sons on 27 April 1887 and was first exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts the same year; the print itself was exhibited at the same venue in 1891. Lord Lever bought The Nest in 1896, from the same art dealers, paying £2,200. It is still in the Lever Collection at the Lady Lever Art Gallery. The print itself was exhibited at the same venue in 1891 and was on tour in Japan until July 2016.

The picture in the Collection is a monochrome print of Millais’ original painting,1887. It is typical of Millais' late sentimental subjects.The printmaker responsible for 215 “The Nest” after Millais is now known to be George H Every and its date recorded as 1890. The British Museum describes him as a 'nineteenth century mezzotint engraver who exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1864'. It has another example of this print which verifies these details: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1893-0718-21. Records at the National Portrait Gallery show that George Every (1837-1910), a London born mezzotint engraver who exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1864-1905, was associated with 56 of their portraits.

'The Magazine of Art' described the painting as:

"suggestive of the Christmas number style of art, dry, disagreeable in colour and steeped in the tritest kind of popular sentiment".

'The Academy Journal' critic wrote:

"there are excellencies of a very high order especially in the head ... but here too a cheapness of sentiment, an obvious disinclination

to deal with the higher elements which even such subjects contain can detract from the enjoyment afforded by the easy mastery of

technical difficulties".

Despite increasingly severe criticism by informed observers, Millais' paintings continued to sell well, as they were calculated to appeal to prospective buyers. The original painting was purchased from the artist by Thomas Agnew & Sons on 27 April 1887 and was first exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts the same year; the print itself was exhibited at the same venue in 1891. Lord Lever bought The Nest in 1896, from the same art dealers, paying £2,200. It is still in the Lever Collection at the Lady Lever Art Gallery. The print itself was exhibited at the same venue in 1891 and was on tour in Japan until July 2016.

The Nest, 1887, by Millais

oil on canvas, 129.5 x 99cm,

Lady Lever Art Gallery

The Nest, 1887, by Millais

oil on canvas, 129.5 x 99cm,

Lady Lever Art Gallery

John Everett Millais 1829-1896

Millais was born on 8 June 1829 at Portland Place, Southampton; his father was a military officer in Jersey. The family, of Norman origin, settled in Jersey prior to the Conquest and remained prominent landholders for nearly 700 years.

The first five years of his life were spent in Jersey, but in 1835 the family moved to Dinan, France, where he began sketching the scenery and local people. These early efforts attracted attention and, aged nine, he was taken to London for an expert opinion on his talent. The President of the Royal Academy, Sir Martin Archer Shee (1769 -1850) was consulted, who declared: “Nature had provided for the boy’s success".

In 1838 Millais entered Sass's Academy in Bloomsbury, under Henry Sass, (1788-1844); an important art school, intended for students seeking to enter the Royal Academy. That same year, surprisingly for one so young, he won the silver medal of the Society of Arts - now Royal Society of Arts - and caused quite a sensation when he stepped forward to collect his prize from the Duke of Sussex at the award ceremony.

In 1839, aged ten, Millais entered the Royal Academy Schools, the youngest student ever, or since, to have been received by them. ‘The Child’ worked hard for six years, taking prize after prize, beginning with the silver medal in 1843 and ending in 1847 with the gold medal for a history painting, The Tribe of Benjamin seizing the Daughters of Shiloh. He continued to paint in the history genre, then considered to be the most important genre in the Academic Hierarchy. His progress, from the point of view of the RA was promising and ‘fashionable’, giving his work a touch of credibility. These expectations were doomed to disappointment; Millais had just been learning his craft and temporarily accepting the precepts of his teachers and fellow students. Millais, at just nineteen, decided that the RA was fundamentally wrong and that there were far better opportunities if he asserted his own independent convictions; from that point his mission in life was to destroy and in 1848 he and his friends formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Ironically, in 1896 Millais was elected President of the RA but sadly it was doomed to be a short tenure. He was in poor health at the time and just six months after his election he died on 13 August 1896, aged 67, and was buried in the Painters’ Corner of St Paul’s Cathedral.

His output totalled over three hundred and fifty oil paintings alone, without taking into account any of his drawings. In an obituary in the Magazine of Art, September 1896, art critic Marion Harry Spielmann (1858-1948) declared:

“now not England only, but with her the whole wide world of art, mourns her greatest painter of the century, the most universally beloved man who through his genius, has ever made his way into the heart and the affections of a nation ……… A life prematurely cut short, has been snatched away, leaving English art deprived of its brightest, if not its greatest ornament.”

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Millais and his friends, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), formed the idea of reverting to a type of art which contained “the germs of great achievement”. They had been inspired partly by Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893) and partly by their own study of the work of the Italian Primitives who, before Raphael, Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), had laboured with devout and simple naturalism. They felt that the principles which guided the early masters, and made their productions so convincing, were being deliberately ignored by the modern art world, whose second-hand practices were based on the conventions created after a long line of degenerate successors of Raphael and his contemporaries.

So these three youths agreed to break away from the rules and regulations which bound their student days in order to proclaim the truths that they felt their teachers had withheld. From this agreement an association sprang into existence, which despite the small number of its members and the shortness of its life, a little less than five years, has left an ineffaceable mark upon the history of the British School. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formerly constituted during the autumn of 1848. It included, in addition to the three originators, two other painters, James Collinson and F G Stephens, a sculptor, Thomas Woolner and Rossetti’s brother, writer, William Michael Rossetti, who acted as secretary. Ford Madox Brown never became a member, although he entirely sympathised with the artistic aims of the group, for he favoured independent action.

At first the inner significance of the movement was lost on the general public. Their work was initially ridiculed, as too was their monthly literary magazine, which declared the Brotherhood’s purpose and intent. The Germ, edited by William Rossetti, published poetry by the Rossettis, Woolner and Collinson, and essays on art and literature by associates of the brotherhood, such as poet, Coventry Patmore (1823-1896). However, it had served its purpose; promotion of the Brotherhood, who were now better understood, and by the time of their next exhibition, spring 1850, so was their work.

Several other young painters, not part of the Brotherhood, started to support them and openly adopted their methods. The list of these outside sympathisers, which included William Bell Scott, Arthur Hughes, Thomas Seddon, W L Windus and W H Deverell, were directly

inspired by the beliefs of the Brotherhood; and if, as would be quite legitimate, it were extended to take in all the others whose first essays in art were controlled by Pre-Raphaelite principles, an astonishing number of artists who have reached high rank in their profession could be added to it. Their most important supporter and patron was John Ruskin,1819-1900, poet, artist, critic, social revolutionary and conservationist. Slowly but surely the Brotherhood gained acceptance and their pictures are as popular today as they eventually became in their own time.

Millais was born on 8 June 1829 at Portland Place, Southampton; his father was a military officer in Jersey. The family, of Norman origin, settled in Jersey prior to the Conquest and remained prominent landholders for nearly 700 years.

The first five years of his life were spent in Jersey, but in 1835 the family moved to Dinan, France, where he began sketching the scenery and local people. These early efforts attracted attention and, aged nine, he was taken to London for an expert opinion on his talent. The President of the Royal Academy, Sir Martin Archer Shee (1769 -1850) was consulted, who declared: “Nature had provided for the boy’s success".

In 1838 Millais entered Sass's Academy in Bloomsbury, under Henry Sass, (1788-1844); an important art school, intended for students seeking to enter the Royal Academy. That same year, surprisingly for one so young, he won the silver medal of the Society of Arts - now Royal Society of Arts - and caused quite a sensation when he stepped forward to collect his prize from the Duke of Sussex at the award ceremony.

In 1839, aged ten, Millais entered the Royal Academy Schools, the youngest student ever, or since, to have been received by them. ‘The Child’ worked hard for six years, taking prize after prize, beginning with the silver medal in 1843 and ending in 1847 with the gold medal for a history painting, The Tribe of Benjamin seizing the Daughters of Shiloh. He continued to paint in the history genre, then considered to be the most important genre in the Academic Hierarchy. His progress, from the point of view of the RA was promising and ‘fashionable’, giving his work a touch of credibility. These expectations were doomed to disappointment; Millais had just been learning his craft and temporarily accepting the precepts of his teachers and fellow students. Millais, at just nineteen, decided that the RA was fundamentally wrong and that there were far better opportunities if he asserted his own independent convictions; from that point his mission in life was to destroy and in 1848 he and his friends formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Ironically, in 1896 Millais was elected President of the RA but sadly it was doomed to be a short tenure. He was in poor health at the time and just six months after his election he died on 13 August 1896, aged 67, and was buried in the Painters’ Corner of St Paul’s Cathedral.

His output totalled over three hundred and fifty oil paintings alone, without taking into account any of his drawings. In an obituary in the Magazine of Art, September 1896, art critic Marion Harry Spielmann (1858-1948) declared:

“now not England only, but with her the whole wide world of art, mourns her greatest painter of the century, the most universally beloved man who through his genius, has ever made his way into the heart and the affections of a nation ……… A life prematurely cut short, has been snatched away, leaving English art deprived of its brightest, if not its greatest ornament.”

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Millais and his friends, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), formed the idea of reverting to a type of art which contained “the germs of great achievement”. They had been inspired partly by Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893) and partly by their own study of the work of the Italian Primitives who, before Raphael, Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), had laboured with devout and simple naturalism. They felt that the principles which guided the early masters, and made their productions so convincing, were being deliberately ignored by the modern art world, whose second-hand practices were based on the conventions created after a long line of degenerate successors of Raphael and his contemporaries.

So these three youths agreed to break away from the rules and regulations which bound their student days in order to proclaim the truths that they felt their teachers had withheld. From this agreement an association sprang into existence, which despite the small number of its members and the shortness of its life, a little less than five years, has left an ineffaceable mark upon the history of the British School. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formerly constituted during the autumn of 1848. It included, in addition to the three originators, two other painters, James Collinson and F G Stephens, a sculptor, Thomas Woolner and Rossetti’s brother, writer, William Michael Rossetti, who acted as secretary. Ford Madox Brown never became a member, although he entirely sympathised with the artistic aims of the group, for he favoured independent action.

At first the inner significance of the movement was lost on the general public. Their work was initially ridiculed, as too was their monthly literary magazine, which declared the Brotherhood’s purpose and intent. The Germ, edited by William Rossetti, published poetry by the Rossettis, Woolner and Collinson, and essays on art and literature by associates of the brotherhood, such as poet, Coventry Patmore (1823-1896). However, it had served its purpose; promotion of the Brotherhood, who were now better understood, and by the time of their next exhibition, spring 1850, so was their work.

Several other young painters, not part of the Brotherhood, started to support them and openly adopted their methods. The list of these outside sympathisers, which included William Bell Scott, Arthur Hughes, Thomas Seddon, W L Windus and W H Deverell, were directly

inspired by the beliefs of the Brotherhood; and if, as would be quite legitimate, it were extended to take in all the others whose first essays in art were controlled by Pre-Raphaelite principles, an astonishing number of artists who have reached high rank in their profession could be added to it. Their most important supporter and patron was John Ruskin,1819-1900, poet, artist, critic, social revolutionary and conservationist. Slowly but surely the Brotherhood gained acceptance and their pictures are as popular today as they eventually became in their own time.

Millais' Connection to Lytham

Autumn Leaves, 1856, by Millais

oil on canvas, 41 x 29 in

City Art Galleries, Manchester

Autumn Leaves, 1856, by Millais

oil on canvas, 41 x 29 in

City Art Galleries, Manchester

It is considered that Millais’ greatest paintings were perhaps his subjectless figurative pictures, The Blind Girl and Autumn Leaves, both 1856. Autumn Leaves was described by the critic, John Ruskin as "the first instance of a perfectly painted twilight." Millais's wife, Effie Ruskin (1848-1854), wrote that he had intended to create a picture that was "full of beauty and without a subject". The picture depicts four girls in the twilight, collecting and raking fallen leaves together in a garden. This painting has been seen as one of the earliest influences on the development of the aesthetic movement.

However, art collector James Eden (d.1874) of Fairlawn, West Beach, Lytham, did not agree. He is often referred to as “the man who asked Millais for his money back.” Eden, along with his friends, art collectors Thomas Miller (1811-1865) and Richard Newsham (1798-1883), excitedly explored the world of contemporary art from the 1840s to the 1860s. Wary of the established art business, they played safe by buying new pictures at exhibitions, including the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in London, and commissioned them directly from the artists. Eliminating the dealers, they struck up close friendships with the artists.

In 1855 Miller and Eden pre-purchased two pictures that Millais was planning to paint for the 1856 Summer Exhibition. Miller bought Peace Concluded for £900 and Eden put down £700 for another Millais picture, though he clearly had little idea what it would be. In May 1856 he set off to the Exhibition as usual and saw his new purchase, Autumn Leaves, for the first time. Eden hated it. Not without reason, since it was quite unlike anything Millais had done before, with none of the Pre-Raphaelites usually meticulous attention to detail. Eden, like many Northern collectors, expected to see plenty of brushwork for his money, but Autumn Leaves looked as though it had been dashed off in a few days. Millais’ biographer, G H Fleming, puts the painter’s change of style down to his recent marriage to Effie:

“I am convinced that Effie was responsible for Autumn Leaves …. she had strong feelings about frittering away time over a picture.”

Whether Eden disliked Autumn Leaves for its own sake, or whether he simply thought he had been done, Miller asked the painter to take the picture back, but Mrs Millais said this was impossible. He never grew to like the picture and got rid of it as quickly as he could. It was sold to another Pre-Raphaelite collector, John Miller of Liverpool.

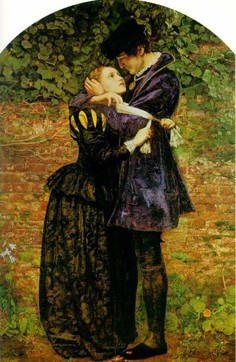

Miller must have been pleased with Peace Concluded, because shortly afterwards he paid £1,000 for another of Millais’ most famous pictures, A Huguenot, on St Bartholomew's Day; Miller probably hung his latest acquisitions at 3 West Beach, Lytham.

However, art collector James Eden (d.1874) of Fairlawn, West Beach, Lytham, did not agree. He is often referred to as “the man who asked Millais for his money back.” Eden, along with his friends, art collectors Thomas Miller (1811-1865) and Richard Newsham (1798-1883), excitedly explored the world of contemporary art from the 1840s to the 1860s. Wary of the established art business, they played safe by buying new pictures at exhibitions, including the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in London, and commissioned them directly from the artists. Eliminating the dealers, they struck up close friendships with the artists.

In 1855 Miller and Eden pre-purchased two pictures that Millais was planning to paint for the 1856 Summer Exhibition. Miller bought Peace Concluded for £900 and Eden put down £700 for another Millais picture, though he clearly had little idea what it would be. In May 1856 he set off to the Exhibition as usual and saw his new purchase, Autumn Leaves, for the first time. Eden hated it. Not without reason, since it was quite unlike anything Millais had done before, with none of the Pre-Raphaelites usually meticulous attention to detail. Eden, like many Northern collectors, expected to see plenty of brushwork for his money, but Autumn Leaves looked as though it had been dashed off in a few days. Millais’ biographer, G H Fleming, puts the painter’s change of style down to his recent marriage to Effie:

“I am convinced that Effie was responsible for Autumn Leaves …. she had strong feelings about frittering away time over a picture.”

Whether Eden disliked Autumn Leaves for its own sake, or whether he simply thought he had been done, Miller asked the painter to take the picture back, but Mrs Millais said this was impossible. He never grew to like the picture and got rid of it as quickly as he could. It was sold to another Pre-Raphaelite collector, John Miller of Liverpool.

Miller must have been pleased with Peace Concluded, because shortly afterwards he paid £1,000 for another of Millais’ most famous pictures, A Huguenot, on St Bartholomew's Day; Miller probably hung his latest acquisitions at 3 West Beach, Lytham.

Bibliography

Baldry, A L, (1889), Sir John Everett Millais : his art and influence, London, available online @ https://archive.org/stream/sirjohneverettmi00balduoft/sirjohneverettmi00balduoft_djvu.txt

Esposito, Donato, art historian

LLAG (2015), John Everett Millais, The Nest, Lady Lever Art Gallery, available online @ ihttp://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ladylever/collections/paintings/gallery3/thenest.aspx

Turner, B, (2011), Victorian Lytham, Lytham St Annes Civic Society, Hersham

Wood, C, (1981), The Pre-Raphaelites, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London

Baldry, A L, (1889), Sir John Everett Millais : his art and influence, London, available online @ https://archive.org/stream/sirjohneverettmi00balduoft/sirjohneverettmi00balduoft_djvu.txt

Esposito, Donato, art historian

LLAG (2015), John Everett Millais, The Nest, Lady Lever Art Gallery, available online @ ihttp://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ladylever/collections/paintings/gallery3/thenest.aspx

Turner, B, (2011), Victorian Lytham, Lytham St Annes Civic Society, Hersham

Wood, C, (1981), The Pre-Raphaelites, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London