Amphitrite/Sea Nymph

|

Research by Hilary Alcock

|

|

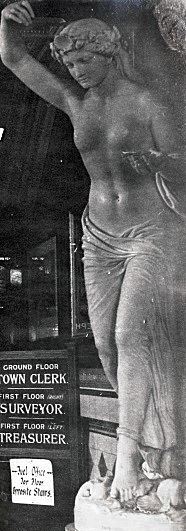

Artist Benjamin Edward Spence Artist dates c.1822-1866 Size height 177.8 cm (70 in) pedestal H78.3 (30.8in) Medium marble Date produced Rome, 1865 Signed and dated 'B.E. SPENCE/ FT./ ROMAE 1865' Donor Councillor & Mrs J H Dawson Date donated 1932 Location Town Hall at St Annes |

This elegant, white marble sculpture takes the form of a semi-naked female with a chaplet (ornamental wreath) of seaweed and shells in her hair. The lower part of her body is classically draped in a flowing robe, her right arm is raised above her head and she is holding a sea scallop in her left hand. (The latter has been quite crudely re-attached and the tip of the forefinger of the right hand is missing). She is standing barefoot upon a rounded-oblong plinth carved with tumbling waves and shells, signed and dated B.E. SPENCE/FT ROMAE 1865. This rests on a rounded, oblong, veined, grey marble pedestal, painted with a gilt presentation tablet, “to the Corporation of / Lytham St Annes /by /Coun. and Mrs J.H. Dawson 1932”.

This sculpture is described as a representation of Amphitrite, the beautiful Greek sea goddess and beloved wife of Poseidon, and her name means “the third one who encircles everything”. She was the focus of many great artworks over the centuries, both sculptures and paintings, by artists such as Nicolas Poussin, Jan Grossaerts (1516) and Regnault, and she even features in one of the cut-out collages by Matisse (1947). Sometimes Amphitrite is characterised with strange little horns like crab claws, a trident and a net, but these are not detailed here, and previous scrutiny of the statue by Sothebys has described it merely as a sea nymph.

However, when researching other similar sculptures of the goddess on Google Images, such as those by Antoine Coysevox Lyon (1640-1720), Lambert-Sigisbert Adam (1700-1759), Eugene Bruchon (1806-1895), and Valentin Eugene Deplechin (1852- 1926), it is clear that Spence’s work is similar in detail to their images, suggesting this is indeed Amphitrite, as Alderman Dawson recorded in his handwritten notes.

ARTIST

It is believed that Benjamin Edward Spence, the son of William and Elizabeth Spence, was born in Liverpool in 1822. He was baptised there in January 1823 at St Peter’s Church (demolished in 1933) in Church Street. His father was a sculptor and as a young man worked with John Gibson at Francey’s Marble Works in Brownlow Hill. He later became a partner in this well-known firm of monumental masons, Spence and Franceys, dissolved in 1819. Before that they were closely involved in the circle of William Roscoe (1753-1831), the great Liverpool art patron, lawyer and a radical politician. It is likely that Benjamin underwent his earliest sculptural training with the firm and by the time he won a place at the Liverpool Academy Schools in 1838, he was already an accomplished and skilful stone-carver. This was the start of a long relationship with the Academy, and Spence exhibited there on almost an annual basis over the next ten years.

In 1844 his statue of The Death of the Duke of York at Agincourt was exhibited in London at Westminster Hall, and a year later his Ulysses was shown at the same venue. Both are now lost, but records show that the former as considered highly enough to be awarded the Heywood Silver medal by the Royal Manchester Institution. Such was the extent of his success that in 1844 young Spence was persuaded to go to Rome, where a small colony of British artists had established themselves. He went at the invitation of his father’s friend and colleague, the Welsh neo-classical sculptor, John Gibson RA, and initially entered his studio as his apprentice but soon moved on to work with Richard James Wyatt. There he adopted a softer, neo-classical, more restrained style, similar to that of Wyatt himself, which reflected the sentimentality apparently popular in the art of nineteenth century Britain. It was during this period that he produced Ophelia (1850) and The Angel’s Whisper (1857). This latter work portrays a winged angel bending over a crib and whispering to a sleeping child. The origin of the piece has apparently several derivations but is most likely to have been inspired by a poem by Samuel Lover; this work was bought by Henry Sandbach for his mansion Hafondunos Hall in North Wales. However, in 1993 it was sold to the Musee d’ Orsay in Paris and is one of the few works by a British artist to feature in their current collection. There is a replica in the Palm House in Sefton Park in Liverpool but it has sadly lost its wings.

When Wyatt died in 1850, Spence took control of the Rome studio and completed Wyatt’s unfinished commissions before moving to the Via degli Incurabili, where he established his own studio and, like other Roman sculptors of the day, built up a wealthy clientele. Each year Spence returned to London to the Royal Academy annual exhibition. However, he was not a frequent exhibitor there and showed no interest in becoming an Academician. He sold the majority of his works directly from his studio, or they were commissioned by wealthy visitors from Britain. In fact Spence only exhibited at the Royal Academy on six occasions. The first was in 1849 with a piece entitled Lavinia, the subject being taken from a poem, 'The Seasons' by James Thompson. This was for Samuel Holme, a builder from Liverpool, who eventually became the Lord Mayor of the city. When it was shown at the RA in 1849, The Art Journal described it as “altogether a work that does great credit to so young a hand”. In 1850 he showed Ophelia, in 1856 Venus and Cupid, in 1861 Hippolytus and in 1867, The Parting of Hector and Andromache. Spence also contributed two works to the International Exhibition of 1862, Finding of Moses and Jeanie Deans.

Spence went on to create many depictions of female figures, including Innocence, Psyche, Rebecca at the Well, and probably his most well-known work, Highland Mary, inspired by Robbie Burns’s poem dedicated to his late common-in-law wife. This was on exhibition in the Library on Fifth Avenue in New York when it mysteriously disappeared, and in its place just a postcard remained showing the sculpture and the descriptive label. It has never been recovered.

To Victorian society, familiar with Burns’s poems, the statue proved to be extremely popular, and in 1853 Prince Albert commissioned a replica as a birthday present for Queen Victoria. It is now one of a group arranged by the couple in the Guard Room at Buckingham Palace, standing next to Gibson’s statue of the queen and the The Lady of the Lake, also by Spence. In 1867 Spence collaborated with Wedgwood as a designer in relation to the pottery’s bisque porcelain or Parian ware, a type of imitation, carved marble. Highland Mary was later mass produced in Parian ware, but Spence also made several replicas in marble, including another one commissioned by Prince Albert, also as a gift for the Queen. It is understood this remains at Balmoral.

Somewhat surprisingly, Spence actually created very few public or monumental works. However, he did carve a figure representing Liverpool for the rebuilt Crystal Palace on Sydenham Hill and, in 1856, a memorial to the Archdeacon of Liverpool, Jonathan Brooks,

for St Georges Hall in the city centre.

On 21 October 1866 Benjamin Spence died of consumption, aged 43, in Leghorn in Italy. He left a widow, Rosina, the daughter of the British consul to Livorno, George Henry Gower. In his Will he left just £1500. By then his gentle, neoclassical style was beginning to look dated, for realism was becoming the style of the day. This is indicated by an obituary in the Art Journal of 1866, (p364), which stated that “Spence was not a great sculptor” and his works “were characterised by a great purity of feeling ….... rather than by much originality of design or vigorous treatment”.

In 1870, when there was a sale of Spence’s studio, interest was limited and prices paid were extremely low. Again the Art Journal made comment, “We feel ashamed to note down the prices paid for Spence’s examples” (p221). To see examples of Spence’s work in public places in Britain today, one should probably visit the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool where there are several examples, as well as to see The Lord’s Prayer, which stands in Sudley House, and there is a sculpture of Sir Joseph Paxton in Derbyshire in Chatsworth House.

REFERENCES

Books:

Honour, Hugh, (1968), Neoclassical style and Civilisation, Penguin,1968

Hussey, John, (2012), John Gibson RA: The World of Master Sculptors, Countyvise Ltd

Irwin, David, (1997), Neoclassicism: Art and Ideas, Phaidon

Macdonald, Lynn, (2010), Collected Works of Florence Nightingale: Travels in Italy and France 1847-48, Wilfrid Laurier Press

Read, Benedict, (1982), Victorian Sculpture, Yale University Press

Ed. Getsy, David, (2004), Sculpture and the Pursuit of a Modern Ideal in Britain, 1880-1930, Ashgate

Articles:

Ward-Jackson, Philip, Victoria and Albert: Art and Love: public and private aspects of a Royal sculpture Collection; essays from a Study

Day at the National Gallery, London, 5 & 6 June 2010

Online:

Henry Moore Foundation

Practice and Profession of Mapping Sculpture in Britain and Ireland,1851-1951

Sydenham Town Forum

Tate, Grant, Simon, 25 March 2014: Why Artists make good Curators

Wikimapia, 1865 Catalogue for the International Exhibition, Dublin, 1865

Wikipedia

Newspapers:

The Evening Gazette, 3 March 1948

The Scotsman, Brown, Craig, 2 February 2007, “Rare statue rescued from the deep”

The Times, 3 February 2007

This sculpture is described as a representation of Amphitrite, the beautiful Greek sea goddess and beloved wife of Poseidon, and her name means “the third one who encircles everything”. She was the focus of many great artworks over the centuries, both sculptures and paintings, by artists such as Nicolas Poussin, Jan Grossaerts (1516) and Regnault, and she even features in one of the cut-out collages by Matisse (1947). Sometimes Amphitrite is characterised with strange little horns like crab claws, a trident and a net, but these are not detailed here, and previous scrutiny of the statue by Sothebys has described it merely as a sea nymph.

However, when researching other similar sculptures of the goddess on Google Images, such as those by Antoine Coysevox Lyon (1640-1720), Lambert-Sigisbert Adam (1700-1759), Eugene Bruchon (1806-1895), and Valentin Eugene Deplechin (1852- 1926), it is clear that Spence’s work is similar in detail to their images, suggesting this is indeed Amphitrite, as Alderman Dawson recorded in his handwritten notes.

ARTIST

It is believed that Benjamin Edward Spence, the son of William and Elizabeth Spence, was born in Liverpool in 1822. He was baptised there in January 1823 at St Peter’s Church (demolished in 1933) in Church Street. His father was a sculptor and as a young man worked with John Gibson at Francey’s Marble Works in Brownlow Hill. He later became a partner in this well-known firm of monumental masons, Spence and Franceys, dissolved in 1819. Before that they were closely involved in the circle of William Roscoe (1753-1831), the great Liverpool art patron, lawyer and a radical politician. It is likely that Benjamin underwent his earliest sculptural training with the firm and by the time he won a place at the Liverpool Academy Schools in 1838, he was already an accomplished and skilful stone-carver. This was the start of a long relationship with the Academy, and Spence exhibited there on almost an annual basis over the next ten years.

In 1844 his statue of The Death of the Duke of York at Agincourt was exhibited in London at Westminster Hall, and a year later his Ulysses was shown at the same venue. Both are now lost, but records show that the former as considered highly enough to be awarded the Heywood Silver medal by the Royal Manchester Institution. Such was the extent of his success that in 1844 young Spence was persuaded to go to Rome, where a small colony of British artists had established themselves. He went at the invitation of his father’s friend and colleague, the Welsh neo-classical sculptor, John Gibson RA, and initially entered his studio as his apprentice but soon moved on to work with Richard James Wyatt. There he adopted a softer, neo-classical, more restrained style, similar to that of Wyatt himself, which reflected the sentimentality apparently popular in the art of nineteenth century Britain. It was during this period that he produced Ophelia (1850) and The Angel’s Whisper (1857). This latter work portrays a winged angel bending over a crib and whispering to a sleeping child. The origin of the piece has apparently several derivations but is most likely to have been inspired by a poem by Samuel Lover; this work was bought by Henry Sandbach for his mansion Hafondunos Hall in North Wales. However, in 1993 it was sold to the Musee d’ Orsay in Paris and is one of the few works by a British artist to feature in their current collection. There is a replica in the Palm House in Sefton Park in Liverpool but it has sadly lost its wings.

When Wyatt died in 1850, Spence took control of the Rome studio and completed Wyatt’s unfinished commissions before moving to the Via degli Incurabili, where he established his own studio and, like other Roman sculptors of the day, built up a wealthy clientele. Each year Spence returned to London to the Royal Academy annual exhibition. However, he was not a frequent exhibitor there and showed no interest in becoming an Academician. He sold the majority of his works directly from his studio, or they were commissioned by wealthy visitors from Britain. In fact Spence only exhibited at the Royal Academy on six occasions. The first was in 1849 with a piece entitled Lavinia, the subject being taken from a poem, 'The Seasons' by James Thompson. This was for Samuel Holme, a builder from Liverpool, who eventually became the Lord Mayor of the city. When it was shown at the RA in 1849, The Art Journal described it as “altogether a work that does great credit to so young a hand”. In 1850 he showed Ophelia, in 1856 Venus and Cupid, in 1861 Hippolytus and in 1867, The Parting of Hector and Andromache. Spence also contributed two works to the International Exhibition of 1862, Finding of Moses and Jeanie Deans.

Spence went on to create many depictions of female figures, including Innocence, Psyche, Rebecca at the Well, and probably his most well-known work, Highland Mary, inspired by Robbie Burns’s poem dedicated to his late common-in-law wife. This was on exhibition in the Library on Fifth Avenue in New York when it mysteriously disappeared, and in its place just a postcard remained showing the sculpture and the descriptive label. It has never been recovered.

To Victorian society, familiar with Burns’s poems, the statue proved to be extremely popular, and in 1853 Prince Albert commissioned a replica as a birthday present for Queen Victoria. It is now one of a group arranged by the couple in the Guard Room at Buckingham Palace, standing next to Gibson’s statue of the queen and the The Lady of the Lake, also by Spence. In 1867 Spence collaborated with Wedgwood as a designer in relation to the pottery’s bisque porcelain or Parian ware, a type of imitation, carved marble. Highland Mary was later mass produced in Parian ware, but Spence also made several replicas in marble, including another one commissioned by Prince Albert, also as a gift for the Queen. It is understood this remains at Balmoral.

Somewhat surprisingly, Spence actually created very few public or monumental works. However, he did carve a figure representing Liverpool for the rebuilt Crystal Palace on Sydenham Hill and, in 1856, a memorial to the Archdeacon of Liverpool, Jonathan Brooks,

for St Georges Hall in the city centre.

On 21 October 1866 Benjamin Spence died of consumption, aged 43, in Leghorn in Italy. He left a widow, Rosina, the daughter of the British consul to Livorno, George Henry Gower. In his Will he left just £1500. By then his gentle, neoclassical style was beginning to look dated, for realism was becoming the style of the day. This is indicated by an obituary in the Art Journal of 1866, (p364), which stated that “Spence was not a great sculptor” and his works “were characterised by a great purity of feeling ….... rather than by much originality of design or vigorous treatment”.

In 1870, when there was a sale of Spence’s studio, interest was limited and prices paid were extremely low. Again the Art Journal made comment, “We feel ashamed to note down the prices paid for Spence’s examples” (p221). To see examples of Spence’s work in public places in Britain today, one should probably visit the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool where there are several examples, as well as to see The Lord’s Prayer, which stands in Sudley House, and there is a sculpture of Sir Joseph Paxton in Derbyshire in Chatsworth House.

REFERENCES

Books:

Honour, Hugh, (1968), Neoclassical style and Civilisation, Penguin,1968

Hussey, John, (2012), John Gibson RA: The World of Master Sculptors, Countyvise Ltd

Irwin, David, (1997), Neoclassicism: Art and Ideas, Phaidon

Macdonald, Lynn, (2010), Collected Works of Florence Nightingale: Travels in Italy and France 1847-48, Wilfrid Laurier Press

Read, Benedict, (1982), Victorian Sculpture, Yale University Press

Ed. Getsy, David, (2004), Sculpture and the Pursuit of a Modern Ideal in Britain, 1880-1930, Ashgate

Articles:

Ward-Jackson, Philip, Victoria and Albert: Art and Love: public and private aspects of a Royal sculpture Collection; essays from a Study

Day at the National Gallery, London, 5 & 6 June 2010

Online:

Henry Moore Foundation

Practice and Profession of Mapping Sculpture in Britain and Ireland,1851-1951

Sydenham Town Forum

Tate, Grant, Simon, 25 March 2014: Why Artists make good Curators

Wikimapia, 1865 Catalogue for the International Exhibition, Dublin, 1865

Wikipedia

Newspapers:

The Evening Gazette, 3 March 1948

The Scotsman, Brown, Craig, 2 February 2007, “Rare statue rescued from the deep”

The Times, 3 February 2007